Ah, I'm bummed. Somebody beat me to this.

Monday, October 31, 2005

Sunday, October 30, 2005

The best of TV, from a bunch of people morally superior to you

The Parents Television Council is one of those Religious Right "watchdog" groups who patrol the airwaves looking for moral terpitude from which to protect us. Dunno about you, but I certainly sleep better at night knowing that Brent Bozell and his cohorts have, at some point during the preceding day, seen something on television that appalled and offended them to their very souls, and, while I am drifting peacefully to sleep, they are curled in the fetal position with their Bibles, mumbling desperate, tearful prayers.

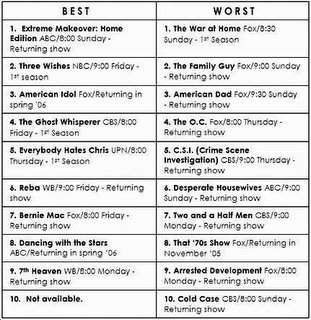

Every year these assclowns fine upstanding pillars of the community assemble their "10 best and worst TV shows list". You know they've had a great year when they boast that they couldn't even find ten shows to put in the "best" category.

Now, I should disclose something right here. I don't watch TV. My industry is film, which is related, I know, but the making of films and TV shows is a fairly similar process and I certainly feel a kinship with the poor grunts who work on them. As a PA I've worked on my share of TV shoots; the days are just as long and grueling, if not moreso, than for a feature. You wouldn't believe how much hard work goes into putting the dumbest programs on the air. One of the best shoots I ever worked on was for a brainless MTV prank show called Boiling Points; I wouldn't watch that in a million years, but I loved earning $150 a day hanging out on South Padre during spring break! What other job offers that kind of guilty satisfaction?

Having stated my solidarity with the poor crews, I'll happily confess: I just have no interest in watching 99% of the feeble crap dished out on the airwaves. I got rid of my cable as I couldn't justify the expense for something I was using less and less. Once in a blue moon, when a show comes on that does impress me (Deadwood), I know there will be DVDs soon to help me get caught up.

So...since I admit I don't like television myself, why do I dog on groups like the PTC who, if you were to ask them, would doubtlessly innocently claim that they're only out there rooting for good wholesome entertainment? Well, partly it's due to their affiliation with the Religious Right, a group we all love to hate. But mainly it's because, as card-carrying RR-ers, they use only the most banal and superficial standards for critiquing shows. Sex, violence and profanity are pretty much it. Incidents of these things are checklisted, regardless of their contextual use in the shows. Any themes — even morally defensible ones — are usually lost in the PTC's obsessive cataloguing of content that triggers their "oh no Billy cover your eyes!" reflexes.

Here is their list for this year:

Now, note what's on the "worst" list: naturally, some of the most popular shows on the air. What's ironic about this is that the far right constantly castigates evil liberal Hollywood for being "out of touch" with what they call "mainstream" (but really mean "their own") values. But if this is so, why are these horrible, evil, amoral shows among the highest-rated? Could it be, perhaps, that most Americans do not, in fact, allow the television shows they watch to dictate their personal morality, but are simply capable of enjoying them as fluff entertainment, even if they have an off-color joke or three? (My parents, devout Episcopalians, love Two and a Half Men. I guess I'll have to phone them and tell them they aren't good Christians now.) Furthermore, could it be that parents are perfectly capable of deciding for themselves what shows are or aren't appropriate for their kids without instructions from self-appointed morality cops like Bozell? Discuss.

Since I don't watch the idiot box unless I'm playing a DVD or XBox game, I thought I'd read what the PTC had to say about some of the shows on their "best" list. About the reality show (I really really hate that term, mainly as I know from firsthand experience working on the crews of some that most of them are actually scripted and/or staged) Three Wishes, this: "This fall, NBC showed us the heights to which reality TV can aspire with its wonderful new series, Three Wishes. The series follows hosts Amy Grant, Carter Oosterhouse, Diane Mizota, and Eric Stromer. Each week the team visits a different town and grants three wishes to various townspeople or the community itself."

Well, that sounds sweet, though I probably wouldn't be a good contestant on it as my first wish would be "I'd like to bang Amy Grant." But look at what they have to say about that evil #1 rated show C.S.I.: "Kicking off the May sweeps on April 28, 2005 with the episode entitled "Committed," C.S.I. delivered a disgusting and depraved hour of incest, murder and even cannibalism... C.S.I. routinely seeks to dwell in the depths of humanity's most dark and evil elements. In “Committed,” the writers sought to entertain the audience through a dark and twisted scenario. It is hard to argue the artistic value of such filth, and it is certainly never appropriate for innocent children to watch."

Though I cannot vouch for the accuracy of all that's portrayed in the show, and I wouldn't deny the use of lurid content to hook viewers (hey, it works!), part of the artistic value of this "filth" is that it is, in the end, a cop show, showing police officers heroically doing the most dangerous thing anyone can do for a living. As sickening as anything the show might depict, if any of the shrinking violets on the PTC's staff were to thumb through the content of some actual police files, they'd have fucking coronaries. Furthermore, C.S.I. has spurred public interest in forensic science and has even prompted juries to pay greater attention to forensic evidence.

So that's the artistic value of that "filth," Brent.

But hey, maybe you guys are right. We should all be watching Three Wishes instead. Then we could all just wish our world free of bad people and crime, and Amy Grant would fly up on her magic carpet and twinkle it all away with a wave of her glittery wand!

Thursday, October 27, 2005

Grr. Arg.

Martin removes, stores brain carefully in jar; manages to enjoy Doom

You know how certain movies come out, and everyone on Earth says "It sucks," and you go see it, and it's not half bad? I kind of had that feeling about Doom, a movie that quite unpretentiously doesn't pretend to be anything other than what it is: a cliché-packed action movie based on a video game in which monsters get shot in dark corridors. Considering that Doom the game is about as reductionist a narrative experience as you could hope for — walk down very dark corridor; boo! monster leaps at you; shoot monster before you become monster chow — the fact that a 100-minute movie could have even been concocted from it is surprising.

I'm a little disappointed that they didn't go with the game's proper concept, that the monsters are actually devils from Hell, as opposed to rehashing some hackneyed drivel about Evil Scientists doing Evil Scientist stuff and learning to regret it. But for the visceral experience of replicating the gameplay — pow! splat! — it got the job done decently well, except for a climactic fight scene that isn't really very Doom-ish at all (more Mortal Kombat). And as threadbare as the story is, I was rather impressed to see the characters faced with a moral dilemma in act three, especially as the whole point of FPS video games is that they give you the cathartic rush of indiscriminate killing without sweating the moral stuff.

No, watching it wasn't nearly as gut-wrenchingly tense as actually playing Doom 3. But for all its predictability, the movie worked for me on the simple level at which it was meant to work, because I could tell these were fans of the game making it, not just cynical studio bean-counters who only saw a hot trademark to cash in on. Oh, I'm sure there was some of that thinking going on at the production end of things. And yet I can easily imagine loads of multiplayer fragfests occuring on banks of XBoxes in the honey wagon between setups. I think the creative team behind the movie really got the appeal of the game as only fans do, and approached the material with the right sense of laid-back fun. For a matinee, it was okay, really.

Now, I loathed the Resident Evil movie, mainly because — well — it played a lot like this movie: a mindless action fest, when it ought to have been a tense and terrifying horror movie. It seems to me that for a video game movie to work, it has to abide by the same guidelines that a literary or comic book adaptation would have to in order to work: understand the source material. Doom: fast-paced action game, gets a fast-paced action movie — check. Resident Evil: moody and creepy horror game with bursts of action, gets...a fast-paced action movie? No no no, not check, big X. Understand what it is you're adapting, filmmakers. Don't just assume that all video games are the same, and since you're making a video game movie, all you have to do is blow shit up. If you're adapting a game whose primary objective is the blow-uppage of shit, then by all means, make that movie. But if it isn't, then stick with the original concept: it's why that game is popular, after all.

As always, the problem is that Hollywood has now made so many bad game-based movies, by people who aren't fans of the source material and don't get what the fans enjoy, that a movie like Doom simply won't catch a break. Bad apples spoiling the batch, and all that. Well, whatever. I didn't feel ripped off seeing Doom. I got what I was expecting. Monsters. Exploding body parts. Gore. Would have liked to have seen Hell, though, rather than that "24th chromosome" nonsense.

Now, if the Silent Hill movie ends up playing like Doom, I'm gonna be pissed!

Yikes!

Okay, so, fresh off my posts about how the internet will end up growing as a distribution outlet for feature films, here comes this news brief from IMDb that packs a pretty high "holy crap!" quotient. A snippet: "A system that would deliver movies and other content to home viewers on demand instantaneously was unveiled today (10/27/05) by Japan's Kansai Electric Power Co., the country's second-largest electric utility firm. The French news agency Agence France Presse reported that the company had developed a technology that can transmit a two-hour movie over fiber-optic cables mounted on power-transmission towers in half a second...."

Brave new world notwithstanding, half a second!? That means that in the time it takes you to read this sentence, you could have downloaded all six Star Wars movies!

I'm gonna go sit down... Oh wait, I am sitting down...

Monday, October 24, 2005

Poor little fella

Hey, I understand. I hate going to the doctor too. All those needles and antiseptic.... Oh, wait, what's that? You just heard Hollywood's remaking Creepshow? Oh god...now you've got me depressed!

Sunday, October 23, 2005

Improving the fate of indie film — part 2 of 2

Long-winded preamble

Ah yes. The plan. It all boils down to digital projection.

Right now, in Austin, there are at least two screens that I know of that are projecting digitally. There may be more, which would be all the proof I need that I have to get out of the house more. But I know for sure of two.

One of them is at the venerable, UT-campus-area Dobie Cinema, which has been around forever and which will continue to be around for as long as the word "forever" has any operative meaning. I've seen it go from a tiny venue with broom-closet-sized auditoriums to its current state, now owned by Landmark, with four nice screens, each in auditoriums done up in clever if kitschy decor (one's ancient Egyptian, one's kind of goth-cathedrally looking, one looks like — well — a regular theater, and I can't really remember what the last one looks like except I do recall I saw all 4½ hours of Lars von Trier's The Kingdom in it, which should clue you in on just how kickass this theater is). Their digital screen uses, last I was there, a Windows Media 9-based projector. Looks all right. I've seen Russian Ark and The Eye on it, and while I was not, in common parlance, "blown away" (which I've always thought sounded too painful to be a good euphemism for "excited" or "amazed" or "real, real happy"), it did the job more than adequately.

The other one is state-de-la-arte DLP projection on one screen at a megaplex, Highland 10. They debuted it with the release of Revenge of the Sith. A smart move; you couldn't get tickets the first week for love or money. As it's kind of a drive from my place, I still haven't yet gotten out to see anything on it.

Anyway. One of the reasons bandied about for why theatrical attendance has fallen off while home theater has caught on has to do with the rapid technological advancements made in recent years in the latter, compared to the nearly nonexistent advancements in the former. Really, the last time I can recall a new technological leap appearing in theaters here was way way back in 1993 (pause a moment to indulge in depression over passing of time and accelerating onset of age), when Jurassic Park opened and debuted DTS sound here for the first time. The audience cheered at the crisp DTS trailer before the movie, and the subwoofers probably did bad things to everyone's kidneys.

But since then — well, we've had more theater closings and re-openings-under-new-management than technological sea changes. What used to be Austin's show-palace theater, the Arbor, was shut down and transformed into a Cheesecake Factory. (Which is a chain of overpriced restaurants, not, sadly, a porn studio.) The Alamo Drafthouse introduced the magnificent innovation of a full kitchen, a beer and wine menu, and no kids allowed. But these weren't so much technological innovations as much as "if I ran a movie theater it'd damn well have..."-style improvements upon the basic experience.

The slowness on the part of theater chains everywhere to adopt digital projection has mostly to do with expense. Each auditorium would, it is estimated, require a refit in the 'hood of a hundred grand to accommodate the new tech. But let's pretend money isn't an issue for a moment (a trick independent filmmakers get really good at, trust me), and imagine how widespread adoption of digital projection could improve the lot of independent film.

First, what if theaters were sent movies not as prints, but as enormous digital files downloaded directly from secure servers — granted, this would have to entail the creation of firewalls that would put the Pentagon's network to shame — to each theater's mainframe? (Geeks reading this will, no doubt, correct me ruthlessly if any of my computer terminology is stuck in the 20th century.)

This would be a Good Thing for indie distributors. One 35MM film print can cost a few grand, and while this isn't as big a speedbump for a studio with billions in assets striking 6000 prints of a surefire blockbuster like Shrek, it is an expense that automatically limits how widespread an indie distributor can get any of his low-budget, specialized-audience films. But if you eliminate the need to strike prints, indie distributors can stretch their tiny budgets much, much further. 35MM, while it is still the optimal choice, is just damned expensive. It's the reason so many indie productions don't even think of shooting on film these days.

Now...here's the clever part. (No no, it's clever. Watch.)

Let's say, with digital projection, you no longer need to have pretentiously titled "art houses" (which, in their current state, could best be referred to as "here's the out-of-the-way theater where we dump all the highbrow shit Jack and Jill Sixpack are too stupid to understand and don't want to see") for the purposes of screening smaller, independent films. Let's say you have a huge, huge megaplex, like one of these 18 or 24 or 30-screen monstrosities. Well, naturally, the majority of that is going to be taken up with Hollywood Product. No matter how big those megaplexes get, they still seem to need no fewer than five or six screens to properly abuse the world with this week's Marvel Comics movie.

But if the movies themselves aren't in the form of cumbersome, pricey 35MM reels, but digital files, life becomes a lot more flexible for the theaters themselves. Let's say Putative Blockbuster you've allocated four screens for turns out to be DOA, like Domino or The Island. Presto, you can yank that peesa shit from most of its screens and replace it with something more profitable in a day, without having to deal with the hassle and expense of a 35MM print that you're under obligation by the studio to have for two weeks at least.

What it also means is that one screen can show more than one feature, even within the course of a single day. And this is where life could get very fun for indie films. Imagine, if you will, that somewhere in the world there's a theater chain whose board of directors can actually mentally process the idea that in an 18 or 24-screen megaplex, one to two of those auditoriums could conceivably be devoted to smaller, independent, or non-mainstream films, and let's move on.

What could this mean in terms of improving an indie film's financial fortunes? I think plenty. But remember my disclaimer: this is all too sensible, and will never happen, because it would require both technological and philosophical innovations that this industry simply isn't poised to make. But in my ideal scenario, it's so crazy it just...might...work...

For my example, I'm going to use an indie movie that's currently in what's politely termed "limited release": the highly-acclaimed Capote, starring Philip Seymour Hoffman, whom Roger Ebert confidently assures me will walk down the Oscar aisles for this. Using box-office figures for the weekend of October 14-16, 2005, Capote, in its third weekend, came in 22nd place on 30 screens nationwide with receipts of $363,876, for a per-screen average of $12,129.

Now, that doesn't sound like much, but in fact, that's phenomenal box office performance. By comparison, that weekend's #1 movie, The Fucking Fog, had a per-screen average of only $3,954. But ah, you see, being Hollywood Product, it was on 2,972 screens nationwide compared to Capote's mere 30. See, that's the thing about indie movies; they don't get the widespread play, but the people who love them damn sure turn out.

Now (I have to stop beginning my paragraphs with that word, I know), think about this. Let's say instead of Capote's being limited in its run to 30 rinky-dink "art houses", it can, due to the "bye bye prints" magic of digital distribution and projection, play on 1000 screens nationwide, on those auditoriums at the backs of the megaplexes that are reserved for such embarrassingly highbrow fare. And then, let's balance things out a bit and require a tradeoff for poor little Capote. Let's say that instead of owning the screen it's on, and getting five showings a day on it, as it would have in the 35MM print days, here, it has to share that screen with two other indie movies. This allows it and the two other movies a total of two screenings per day, like so:

Capote: 10:00 AM; Movie #2: 12:30 PM; Movie #3: 3:00 PM; Capote: 5:30 PM; Movie #2: 8:00 PM; Movie #3: 10:30 PM

So instead of getting, over the course of a weekend, an average of 15 showings, Capote is getting six at most. Because of this, let's reduce Capote's fortunes even more. Let's knock its per-screen average by a full two-thirds! Ouch. Hey, $4,039 is still a nice performance, and still better than that of The Ass Remake I Refuse to Dignify with the Name of The Fog. Now, let's look at how much money Capote takes in over a weekend, shall we? Drum roll, please — $4,039,000. Nice. Much nicer than $363,876. On 1000 screens, of course, but with fewer than half the showings, mind you.

Yes, I know this all pie in the sky stuff. But dammit all, it seems so...so...so feasible, you know, when you ignore little annoying facts like the necessity to redefine theatrical distribution and exhibition as we know it before it could even be implemented. But crazier ideas have been seen through to fruition before, you know. That we even have movies at all is attributable to just such crazy idea-making. For the world in which we live, I imagine DVD and the internets will have to be the great white hope for indie films, realistically speaking. But I'm just old fashioned: movies, still, are best seen in theaters, and it would be great if more movies had that chance, and if a better structure were in place to make it happen.

Cripes, that was long. Me for some caffeine.

Friday, October 21, 2005

Thursday, October 20, 2005

Quickie: The science fiction movie canon according to Scalzi

The brilliantly entertaining science fiction writer John Scalzi has just released his nonfiction work The Rough Guide to Sci-Fi Movies, and, like many books of that type, he's included his own best-of list or "Canon," a list of the 50 SF movies you must see before you die. This list is already circulating around the blogosphere, with everyone taking the predictable hits: "Why is [X] on there and not [Y]?"

Naturally I have my own critiques — 28 Days Later? I thinketh notteth — but overall the list seems fairly sound, and the book looks entertaining and quite thorough in its analysis of the history of SF in film. Can't wait to get my copy.

"Best of All Time" lists are a common critical tradition, and the tradition raises the question of why such lists ought to be prepared in the first place — as art is all a matter of taste, right? Sure, to a certain extent. But art never exists in a vacuum. The fact that not everything appeals to everyone's tastes is kind of beside the main point, which is that in every artistic field, there come certain examples of work that just plain make history. Either they just hit at the right time; or they strike a chord with the public and develop an enduring appeal; or, filmmakers, critics and academics can analyze them for revolutionary use of technique that goes on to influence later generations.

This is why you keep seeing many of the same movies like Citizen Kane, Casablanca, and Gone with the Wind popping up on lists like the AFI Top 100. They are, of course, widely beloved, but not by everyone. The den of your average doublewide is more likely to be inhabited by dudes drinking light beer and chortling to Happy Gilmore than by chaps in tweed furrowing their brows and gnawing their pipe stems over the existential angst of Through a Glass Darkly. But what's more important than these films' popularity is their enduring legacy of shaping the way films were made for years afterward. Influence, innovation, and artistry are more relevant than popularity when establishing a canon. A canon is not a "my favorites" list, it's a "most important to the art form" list. And a wise person will recognize when a work of art is important to history even if it's not their personal cup of tea.

So this is why, for instance, if I were coming up with a horror movie "canon," I'd have to add something like The Blair Witch Project, though I don't think much of it as a movie myself. Its importance in legitimizing indie film (to whatever small degree) and its influence upon microbudget digital filmmakers everywhere is indisputable. (Also, a horror canon would have to include The Exorcist, a movie I personally find silly, boring, and atrociously written, but whose status as a cultural bellwether one would have to be a fool to deny.)

Finally, the relevance of best-of-all-time lists is that, even if it's only to a very abstract degree, they give artists a consensus standard of excellence to aspire towards. I don't think anyone today (except a few pretentious wankers who shalt remain nameless) makes films with the explicit hope of ending up on such a list years hence. But show me a director — outside of, naturally, the obvious schlockosphere trolled by the likes of, say, Troma — who wouldn't smile at the thought that, someday, in fifty or 100 years, their movie is being taught at universities alongside the work of Welles, Scorsese, Fellini, and others, and I'll show you a lying liar.

Improving the fate of indie film — part 1 of 2

A huge stumbling block for even a well-made independent movie is that of securing reliable theatrical distribution.

If no one ever sees your movie, it's a huge blow. You might as well have never made it. With distributors demanding a cast that includes at least one recognizable name — and that of a movie star; TV actors cannot cut it — and an easy-to-grasp, high-concept premise that can be easily advertised, it's getting next to impossible for little labor-of-love movies to find an audience. Every once in a while a fluke success like El Mariachi or The Blair Witch Project pops up, fills the fevered brains of eager microbudget filmmakers with unrealistic expectations, and voila, 2500 undistributable pieces of shot-on-mini-DV crap are ejected into the world with a squint and a grunt. I was an A.D. on one such, and it was painfully obvious to me all through the shoot that this little movie was going absolutely nowhere. What's more depressing, an unrealized dream, or a feebly-realized dream that will be greeted with categorical indifference by the world?

But...let's say you've made a good indie movie. Let's say you actually got a decent budget, maybe even a couple million bucks, got a credible name or two. And you shoot the thing, and it looks money. And you hit the festival circuit. And it sells. Someone hands you a check large enough to bring tears to your eyes, and you have a distributor!

Now what?

I happen to have worked on one like that, too.

I was a PA for a week on a $2 million family film called When Zachary Beaver Came to Town, about a 650-pound boy, shot around the Austin area in September/October of 2002. It was my first professional film crew gig, and the numerous subsequent jobs I've had have helped me to realize just how much — from a production/organizational/having your shit together point of view — of a wholly incompetently run clusterfuck that shoot was. But that's another tale for another day. What's salient to this post is that this was, by industry standards, a respectable kind of indie production. Decent low budget, a cast that included Eric "I'm in Everything But Somehow Still Have Spotless Cred" Stoltz and Jane Krakowski, then still hot off the set of Ally McBeal. The director, a goofball named John Schultz, had just directed something really, really stupid called Like Mike, which, like so many really, really stupid movies, was a studio production that had taken in $50 million. Schultz earned undeserved clout, that he later used to direct an African-American remake of The Honeymooners in 2005, a movie that currently stands at #29 on IMDb's "Bottom 100" list. I don't usually like to rag on directors when my own career is in its nascent stages, but as I haven't made the 29th worst movie of all time, excuse me if I feel justified in the use of such a mild sobriquet as "goofball".

Zachary's saga is then fairly typical of a small indie production. It did the festival circuit for two whole years at least, after which it was picked up by Echo Bridge Entertainment. I've never heard of them either. The IMDb page has a "limited" US theatrical release listed for January 21, 2005. Must have been really limited, as it never played here, the town where it was shot. I cannot confirm the reality of this release at all, as a search of Box Office Mojo, which tracks everything that plays in U.S. theaters even if it only hits one screen, turns up nothing. The movie's site now lists a DVD release date of January 3, 2006. (Addendum 10/22/05: Just found out that it's playing right now on England's Sky Movie cable service.)

So the long and short of it is that, three years and three months after it was shot, little Zachary will be dumped directly onto DVD. Its tweener child stars have by now flown through puberty, and one or two of them might even have their driver's license. And this movie is one of the lucky ones. Really makes all the sunburn (I earned the nickname Pinky for foolishly failing to apply sunscreen on day 1; by day 3 the set medic was ordering me to wear a hat) and those 15-hour days seem worthwhile.

The feeble distribution possibilities open to independent movies got me thinking — as I'm sure it gets everyone in this business thinking who works at this scale — about how these films could get a better chance at finding a receptive audience. Direct-to-DVD isn't such a curse, really, and even a number of studio films that didn't catch fire at the box office suddenly found a horde of enthusiastic fans on DVD (vide Office Space). But we still live in a world where playing in theaters is seen as a sign you've made a real movie; direct-to-video, even direct-to-DVD, still carries the not-exactly-unjustified taint of "Oh, couldn't get it in theaters, eh? Must really be crap!"

I've thought of a way to get indie movies into more cinemas that could work. The problem is, this isn't Utopia, it's Earth. And so it wouldn't work here, simply because it will never be implemented. It will never be implemented for, I think, two crucial reasons. It involves revolutionary new technology that theater chains have so far powerfully resisted, mainly for the entirely reasonable reason of expense. But mainly, my idea would never be implemented because it would require the entire industry to adopt a sea change in its thinking, to stop automatically shunting every movie ever made into two categories — the commercial, pretty much always studio-backed films that everyone really really wants to see (except when they don't, as the weeping producers of Bewitched and Stealth and The Island will attest), and the "art product" (I shit you not, I've heard that term with mine own ears) that no one except college kids and poncy intellectuals wants to see. My idea would require the industry to think of movies just as movies, either good or bad on their own terms. And that will never happen. But hey, dream with me here a little bit. Tomorrow, I'll outline my plan — which I've even worked out with, like, math and stuff — and we can all, for one bright, shining moment, live in the world not as it is, but as we would like it to be. And then, those of us who make movies will get right back to work, laboring over our labors of love with all the passion we can muster, regardless of what distribution opportunities await us — or don't, as the case may be. Because we'll never have the world we want unless we learn to work within the world we have, will we?

Tuesday, October 18, 2005

Okay...deep breath...inhaled...released...

Apparently the rumors of a Weinstein-excreted Halloween remake have all been a tad premature. Still, the news was, for a while there, nearly as scary as the original movie. Of course, what is in the works (Halloween 9) doesn't exactly make me giddy with joy that life now suddenly has meaning and hope, either. Pointless sequels inspired by greed are only slightly lower on the food chain than pointless remakes inspired by greed.

In a related bit of news from the world of comedy, Sylvester Stallone is prepping Rocky 6.

Back soon with those promised posts about worthwhile remakes, and how new distribution strategies (that will never happen) could boost the presence of indie film.

Monday, October 17, 2005

I think I've found my next production designer

Whoever creates something like this is a man after my own heart!

Quickie: Daniel Craig + Bond = way cool

While I mean for this blog to be largely free of fanboyish twaddle (visit this well-known site for that), allow me quickly to jut my thumb in an upwards fashion over the choice of Daniel Craig as the new Bond. Are you telling me you haven't seen Layer Cake? Hie thee to Netflix, varlet.

Brosnan was actually a terrific Bond. But oy, those scripts. A downward spiral from the get-go. GoldenEye — fine, fine. Tomorrow Never Dies — watchable only for Michelle Yeoh, really; would have been much better had they not chosen to off Teri Hatcher in act one, too. The latter two — urk.

Quentin Tarantino's proposed version of Casino Royale with Brosnan will have to remain one of cinema's great "if onlys." The Bond movies have always been "producer movies." It appeared, for many years, that they were more than that; they were "stupid producer movies," given the series' forward-march into pure comic book territory ever since...well, Moonraker. (Not to mention the fact that anyone who turns up their noses at a pitch from QT is not, to quote Black Adder, "exactly over-furnished in the brain department.") Tarantino wanted to bring the series back to Ian Fleming's original low-tech, character-and-drama oriented vision. Now the rumor is, with the new Craig film (which, amazingly enough, will be Casino Royale), the producers actaully want to do that, too. Hiring the screenwriter of Oscar-winner Million Dollar Baby shows they have their heart in the right place. The only problem I foresee is the return of GoldenEye helmer Martin Campbell, a member of the subspecies Genericus Directorius Hackibus. I try not to dog on directors named Martin, but I haven't seen anything of his (including Zorro) that didn't look like it was directed out of a manual.

I fear that the sheep will give Craig the same brushoff they gave Timothy Dalton, who I thought was a badass Bond who fit the rough-edged template I felt the character needed. (Fleming described Bond as good-looking in a "cold way".) Did anyone actually believe that Roger "You Will Never See a Single Strand of My Expertly Sprayed Hair Out of Place" Moore was a trained killer? But I fear too many folks prefer the image of Bond-James-Bond as the martini-swilling pretty-boy seducer than as anything resembling a tough, take-no-prisoners action hero who'll jack you up soon as look at you. But we'll see. All they have to do is put out a damn good movie for a change, and the audience might just decide that "ugly" Craig guy's all right.

So...please please please don't suck. Okay?

iTunes for movies? Will downloads supplant theaters? Discuss.

God, I love my iPod. This is one of those culturally-paradigm-shifting inventions, like the automobile and toaster, that gets you thinking that life must have been a bleak and meaningless wasteland before it came along. It's enough for me to take pity upon the forgotten portable CD player nestled, alone and forlorn, in a drawer in my bedroom. Don't be sad, little fella. You done good. But it's a new day. For you to do the job my Pod does, I'd have to hump around my entire CD cabinet everywhere I go on a dolly. So enjoy your rest. You've earned it.

Now along comes the new video-playing model, and I'm like, damn. Will have to add that to the want list now. And its existence seems to be bearing out what I and the rest of the world have been predicting: it's only a matter of time — months, perhaps — before someone figures out a workable model for distributing feature films online. And I bet Steve Jobs will lead the pack.

Now as a cinephile, I must say I'll be sad if the theatrical experience ever goes away entirely. And to be truthful, I don't think it will. There's nothing that can compare to seeing movies the way they were meant to be seen: on a whopping great screen in an auditorium.

But, believing that, why don't I go more often? I read the polls conducted by the panicked industry and I hear many of the same concerns I have. It's too pricey (although it isn't pricey for me, as I never allow myself to be robbed at the concession stand; eating and drinking in a movie invariably has me running to the men's room just as the third act is kicking in). Other patrons are pricks. The movies mostly just suck.

People are getting used to a more personal entertainment/information experience. Big screen home theaters are more affordable, and will get more affordable still. More and more people have laptops, iPods, and PSP's; pretty much everyone has a cell phone now, perhaps even some homeless people. Are we forsaking communal experiences for individual or family-centric ones? And is that really a bad thing?

It's inevitable that the internet will become a huge distribution outlet for feature films. While I don't see much benefit in watching something genuinely epic, like The Return of the King or Kingdom of Heaven on an iPod's 2-inch screen, there is something to be said for film distribution following the iTunes model for music distribution. Imagine paying about what you'd pay, if not less, for a movie ticket these days to legally download a first-run feature film in DVD-burnable, high-definition quality. Hell, with extras, even. I'd be interested, and I bet lots of other folks would, too, though of course there will always be that contingent of cheap bastards who don't want what they can't have for free. (Hey, I've been one myself.) And I think theatrical exhibition could be saved, too, made attractive again in the eyes of filmgoers, if a few technological (as well as attitude) changes were made by the industry. In my next post I'll go into some ideas I've been chewing on for both enriching the theatrical experience as well as enlarging the share of the pie that poor, also-ran indie films usually get. It's utopian stuff, and it'll never be implemented because the industry would never do anything either a) so sensible or b) designed to get anything seen by the public that isn't their homogenized, generic crap.

But hey, this is my perfect world we're talking about here, so here, it would work!

Sunday, October 16, 2005

Why I won't go see The Fog; musings on remake mania

Hollywood is remake-happy these days. Remakes are hardly a new concept. They've been around since the Golden Age, and some of the biggest movies of all time have been remakes. The Charlon Heston version of Ben-Hur was a remake, and Cecil B. DeMille's cheesy disasterpiece The Ten Commandments was a remake of a version he himself had made in the silent days. Remakes, like shit, happen.

There is nothing innately wrong with remakes simply because they are remakes, either. One of my all-time favorites, and one of the best modern horror films, is John Carpenter's 1982 The Thing. (But then Carpenter went on in 1995 to do a perfectly dreadful remake of his own, Village of the Damned.)

There is an easy and obvious test to be conducted, that can help the hapless viewer determine whether or not a remake is worth seeing. And Carpenter's Thing aces the test. It's simply this: Determine whether or not the remake in question was put together by a filmmaker who passionately loved the original material and felt there was something legitimate to be done artistically in developing a new version, or whether the whole thing is a purely commercial exercise cynically slapped together by a studio desperate for some easy box office green.

Carpenter just happens to be a plum example of the trend, because in 2005 we've had no fewer than two remakes of old movies of his. I've seen neither the new version of Assault on Precinct 13 or The Fog, and don't plan to. In the case of the latter, it's that every reliable source I've heard has confirmed every initial fear I had: that it doesn't simply suck, it creates a cinematic black hole in the theater, a singularity from which not even light can escape. As far as Assault is concerned (the original version of which, interestingly, was Carpenter's own exercise in a modern-day remake of the western Rio Bravo), I do understand the filmmakers attempted a new angle on the story. But if you ask me, replacing the menacing, faceless street gangs outside (inspired by Night of the Living Dead) with the cliché of corrupt cops is a yawn-inducer. Much as I like both Ethan Hawke and especially Laurence Fishburne, I just can't work up any interest in the movie.

And that's because I think both of those movies fit the latter of the two determining factors I outlined above. These were commercial exercises, not creative ones. Yes, I know. Hollywood is all about the money. But when I hear that a remake of Halloween is in development — the original, sacrosanct, impossible-to-improve-upon, often-imitated-but-never-duplicated Halloween — suddenly, suicide bombers seem like reasonable guys. (That was a joke, all you Patriot Act types.)

A remake of Halloween ought to be enough to make any horror fan's blood boil. That it is being thrown together by the Weinsteins, who were responsible for the last handful of appalling sequels and whose shameless prioritizing of their own bank accounts over the success of the movies they were supposed to be distributing is given a full accounting here, is, I suspect, no surprise. But what depresses me is that they're going to make the damn thing, and the sheep will flock to theaters to see it the way they did The Fog this weekend. (Though that was only to the tune of $12 million, it must be said.) Hollywood moguls can treat their audiences with contempt by releasing Product (and that's all it is) like this, and, even though the numbers are dwindling, enough people will go see the Product that in their minds, the entire exercise is justified.

Ah, but there are those dwindling numbers, aren't there? And a lot of that is what I think accounts for the current outbreak of remakes. After all, if it seems like we've been getting more of them in the last few years than is usual, I think the plummeting box office that has had the industry in a panic could very well account for why we're seeing so many studios going the "easy money" route.

But can any of these remakes really generate the massive, $100-million-plus B.O. receipts every studio wants? They can, if the remake in question really makes a stab at reinventing the material for a new audience, and does so in a way both respectful to the source and to creating something sorta fresh at the same time. Not being an Adam Sandler disciple, I avoided The Longest Yard, and critics predictably savaged it, but it did find a receptive audience. The same cannot be said for the aforementioned Assault and Fog, or others we've had this year like The Amityville Horror. Whatever the moguls seem to think about the safety of pursuing remake projects, for the most part audiences seem to want to see new movies, like March of the Penguins and The Wedding Crashers.

In a subsequent post I'll talk about some remakes I've liked and why I thought they worked well. But when it's so obvious that the love of money rather than the love of movies is motivating a remake project, I just vote with my dollar and don't go. And, if the relatively weak #1 of The Fog is any indication (compare this to the $40 million opening of another remake, The Grudge, a year ago), audiences are doing more of that too. There are too many promising writers, and too many good unproduced scripts out there, to waste time on remakes. But what can you do against the machine? Well, fight harder to get your movie made, that's all. Then, if you're really lucky, 20 years some now some sleazy producers will be remaking your low-budget labor of love as a slick piece of assembly line hackery. You'll really know you've made movie history then!